‘Hitting the Edge of the Pingpong table’: An Interview with Wang Qingsong

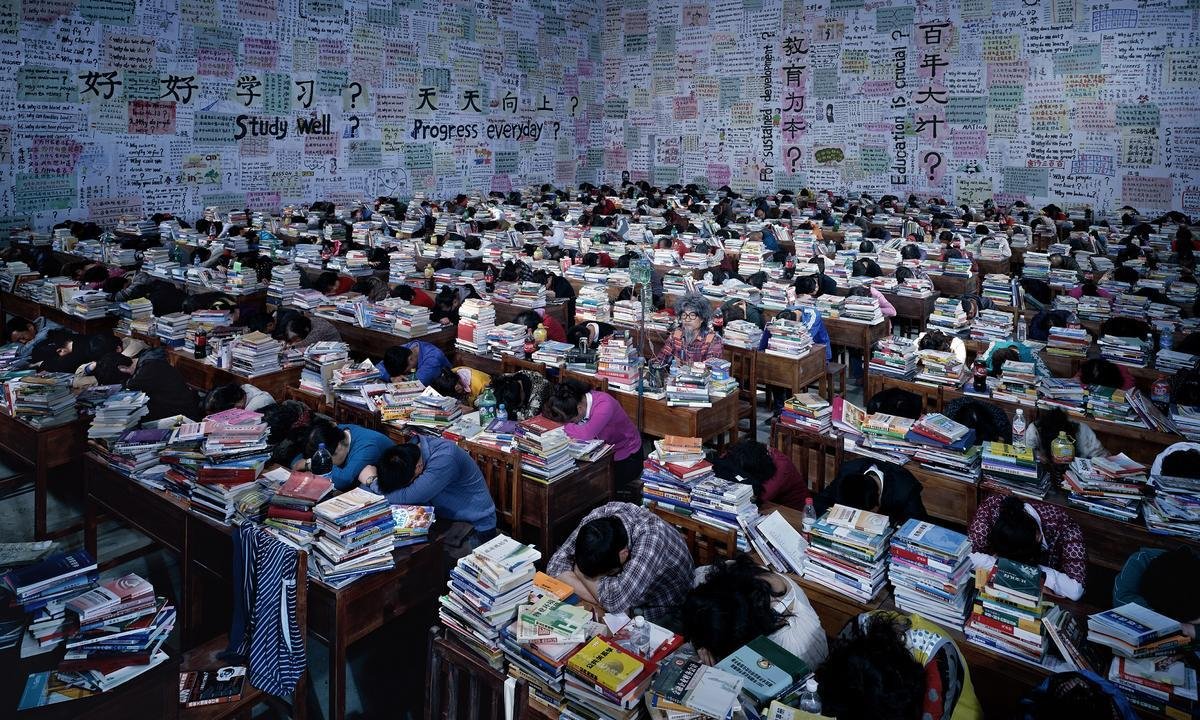

To mark the opening of Wang Qingsong's solo exhibition, Everlasting Inscription at UWA’s Cullity Gallery, we’ve decided to revisit an interview we conducted with the seminal artist for our 2024 China Trip. One of China's most influential contemporary artists, Wang Qingsong’s work often tackles the issues faced by Chinese society in the wake of the reformist era of the 1980s. Wang Qingsong is perhaps best known for his large-scale photography, capturing scenes of chaotic action, whether it's a hundred or so worshippers praying before an enormous statue of the Buddha or a solitary man obscured by the thousands of well-read books around him. While not all of his work is characterised by intense action, one recurrent theme is a proverb that Wang Qingsong described at one point in this interview: ‘hitting the edge of the Ping-Pong table’. Wang Qingsong does not describe himself as a political or social activist, but rather as a recorder of Chinese society. Therefore, the proverb he describes highlights the work. Rarely does his work directly confront the issue he is attempting to record. Instead, it operates in an observatory role, focusing on these issues in dramatic scenes to allow Wang Qingsong to record their extent. On that note, we thank Wang Qingsong for his time, and we hope you enjoy the following Interview

Wang Qingsong discussing his work at UWA’s Cullity Gallery, 2025

Photograph taken by author

Tami: Let’s start with the first question. Your work deals with alot of sensitive topics. What is your approach to avoiding censorship?

Wang Qingsong: My work does address controversial subjects, but it’s also been exhibited publicly many times. The key is learning how to explain yourself. I try to avoid using obvious symbols of opposition because I’m not trying to criticize society directly. My work raises questions about China’s development process rather than issuing direct critiques. That’s why question marks often appear in my work — they’re about raising doubt, not confrontation. Society is developing rapidly, and there are many issues, both good and bad. These questions are a fundamental source of my creativity. I don’t frame my work as social criticism. I’m just raising questions. Doubt is the starting point for reflection.

Tami: So your work is more reflective than oppositional?

Wang Qingsong: Yes. Sometimes I have doubts about society, and having those doubts allows you to think more deeply. That approach makes navigating sensitive situations easier.

Tami: You mentioned something about “hitting the edge” — could you explain that?

Wang Qingsong: Yes. In Chinese, there’s a term, 擦边 (cā biān), which literally means hitting the edge of a ping pong table. It’s like addressing sensitive issues carefully — touching the edge without toppling the whole game. You’re raising questions while staying within the limits, so your work can exist publicly and still “win the game,” so to speak.

Tami: So you approach censorship tactically?

Wang Qingsong: Yes. I see myself more as a journalist than an artist — observing, recording, and reflecting life. My work is like a fine embroidery needle: subtle and precise. It pricks the nerve rather than confronting society aggresively. That’s why it can be shown publicly — it’s a reflection of social reality rather than a statement of opposition. Exactly. I don’t see myself as creating activist art. My work is more like that of a correspondent — recording society and social risks, rather than fighting against anything.

There’s a Chinese proverb that motivates me: 笨鸟先飞, “The slow bird flies first.” It means if you feel you’re not particularly smart, you have to work harder to keep up. But in China, it’s complicated. Sometimes if you “stick your head out,” you’re vulnerable — like the proverb 槍打出頭鳥, “shoot the bird that sticks its head out.” So, if you’re not strong yet, it’s better to listen, stay low, protect yourself, and move forward slowly.

Wang Qingsong Dormitory (2006)

Tami: So discretion is a form of survival?

Wang Qingsong: Exactly. In Beijing, the environment is complex, and control is strict. I came alone, so I had to protect myself first before I could slowly integrate into the city and society. Staying low allows you to survive and navigate safely. By quietly observing my surroundings, I gradually formed an understanding of the world. I like sitting quietly, absorbing a place, feeling it. That became central to how I create.

Tami: Did this habit start in school?

Wang Qingsong: Yes. Even in school, teachers didn’t remember me because I was average. But I observed closely, kept following, paying attention. Later, in society and in Beijing, I stayed under the radar, quietly working and creating. Even when others tried to document artists in places like the Yuanmingyuan Art Village, they couldn’t find me. There were no photos of me because I wasn’t visible.

Tami: So your approach is about observing, recording, and understanding rather than confronting?

Wang Qingsong: Exactly. I record society and its realities, but I don’t try to fight against it. Staying low, cautious, and observant has been my strategy for both survival and creative practice. When people tried to document the artists at the Yuanmingyuan Art Village for archival purposes, they realized they simply couldn’t find any pictures of me—there was no record. Later, people thought I was one of the most important figures at Yuanmingyuan. They asked me, “How could there be no photos of you from that period?” I told them that many people did try to photograph me. I knew that for certain. But no one actually did because, at the time, even if I got a bit angry, I sometimes asked them to photograph me, and they would say, “You’re not important. Why would we photograph you?” So, essentially, I remained in this process quietly.

Tami Xiang: After your exhibitions, do you notice anything different about how people interacted with your work?

Wang Qingsong: Yes. After exhibitions, I realized each show created a kind of expectation—people wanted to see where I would “stand” in relation to the work, or how they could experience it. Early on, none of my obstacles were created by curators—they sometimes gave me opportunities, and I noticed people observing others, then turning to me, hoping I would go to a certain spot. Exhibitions became a cycle: not just people discovering your work, but observing it in situ, seeing how it functioned in real time. This is the way I think, and it shaped my development. Even now, when I go to international exhibitions, I observe carefully. I notice things from perspectives others might find artificial. I pay close attention to how long I stay with it, how I experience it. I don’t rush or ignore it—I think this longer, slower engagement shapes the way I move through the work.

People might not notice, but it matters to me. Back then, when I became more known, people would try to find pictures of me. But they couldn’t. So usually, people knew me only through exhibitions—even when I had shows, there were no photographs documenting me. But I generally avoid large summary exhibitions. I don’t like being tagged into things, put into texts or narratives by others. I prefer to stay low-key. But I still maintain good relationships with officials. They might invite me to meetings or exhibitions—I say, “Sure, no problem.” But I refuse to take group photos. If they publish it in the news, I don’t want my image used. That’s how I protect myself. I’m not opposing anyone, but I avoid being the “head bird.”

Tami Xiang: What kind of equipment do you use in your work?

Wang Qingsong: I use large-format cameras. Currently, all my prints are 12 by 20 inches. The negatives are very large, which allows me to develop prints up to 1.8 meters. The technology is important, especially in China, where documenting society is complicatedu, society changes fast. If you leave for three years, come back, and everything has been demolished, those records are vital. Photography captures rapid social changes, dramatic events, and even everyday realities. For example, in China, there are tens of thousands of unnatural deaths among minors every year. These events, and the emotions around them, must be documented.

Tami Xiang: And did you try other ways to document society?

Wang Qingsong: Early on, I even attempted to use a fake journalist credential. But it was difficult. Photography became the most effective medium for me. In contemporary China, photography is crucial—it’s one of the few ways to record these changes accurately.

Tami Xiang: So photography is more than an art form for you—it’s a record of society?

Wang Qingsong: Absolutely. Social changes, rapid development, housing prices skyrocketing over decades—these are realities that can disappear overnight. Photography allows me to confront and capture these transformations.

Wang Qingsong Dream of Migrants (2005)

Tami Xiang: So why did you choose photography, even though you studied oil painting?

Wang Qingsong: I think it comes from my perspective on China. I studied oil painting, but I chose photography because I saw China was on the verge of major changes. It started around 1992, with a very important moment—the Southern Tour of Deng Xiaoping. After that, China’s real market economy began. I saw the country opening up to markets, and in 1993 I came to Beijing. I witnessed the city’s transformation firsthand. I had been painting for two years, but I realised painting couldn’t capture the speed and complexity of the changes. Photography, I felt, was more direct and real—it could better express what I wanted to convey.

In the 1990s, things were changing quickly. Our former model—the Soviet Union—collapsed, the Cold War ended, and China was facing a new reality. The country had to open to the West, which led to globalisation. At that time, Western goods, ideas, and cultural forms entered China. It started with physical objects, then ideas and cultural exchange. By the 2000s, China was hosting major international conferences and, by 2008, the Olympics—globalisation in full effect. Many journalists even used my work to illustrate globalisation. At first, I didn’t understand how that could happen—I was creating art, not journalism. But my work condensed the essence of globalisation, showing China as a vast landscape transforming rapidly. I realised my ideas and work needed to evolve alongside these societal changes. China became a market-oriented society, galleries emerged, and the country itself was transforming. I had to keep pace with these changes, and photography became the medium that allowed me to do that.

Tami: In your studio area at Caochangdi, did other artists influence you?

Wang Qingsong: Not really. I was one of the first to move in, so other artists didn’t affect me much. My inspiration mostly comes from society, from people outside the studio. This life—observing the city, the people—that’s been my greatest influence.

Tami Xiang: So you weren’t much influenced by your neighbors?

Wang Qingsong: No. We drink and eat together, become friends, but we never really talk about art. Even if I talked a lot, it wouldn’t affect them. For example, I’ve lived next to Ah Chang for over twenty years—we’ve never discussed art. I’ve never attended his performances either.

Tami: How do you experience other artists’ work then?

Wang Qingsong: I might observe from a distance or watch recordings. The point is that even without direct conversation, you can understand society through their work—through their bodies, their actions. It’s a way of sensing how the world moves, a kind of physical understanding of social dynamics.

Wang Qingsong Work, Work, Work (2012)

Tami Xiang: So your approach is shaped more by life and society than by other artists?

Wang Qingsong: Exactly. Life, society, and the people around me have always been my greatest influences. Art practice is secondary—it’s a tool to record and engage with reality. We gossip, eat, drink, live together. That’s where inspiration comes from—not formal artistic discussion. We just chat about life—“How’s that person doing? What’s their situation lately?” Even if we move around a lot, best friends still stay close. We stick together, inseparable, affecting each other in many ways.

Tami: You mentioned using Photoshop versus building physical stages for your work. Do you think using Photoshop changes the meaning of your work?

Wang Qingsong: Yes, it does add some pressure. It’s related to each person’s working habits. I used to work as an oil worker for seven or eight years, so I value labor in my work. If a piece involves real labor, it feels more meaningful. I always consider myself a “not intelligent bird”—I don’t rely on cleverness, but on effort and hard work. I did try learning Photoshop in the 1990s to manage relationships in my work. I even took a course, but I couldn’t learn it. I tried multiple times, paid for classes, but it never worked. So I quickly switched to film photography and stopped using digital tools. I still don’t use a computer today. If someone is tech-savvy, Photoshop or digital tools can be interesting, but for me it’s very difficult. Even small actions require someone else to help. Once you rely on other people’s technical skills, your work will inevitably be influenced by them. I want to labor on-site, building stages like a worker, because that physical involvement matters to me. Assistants are just workers—they follow your instructions. With Photoshop, there’s more artistic skill involved, but it’s still a purely technical function. My assistants are like construction workers—they don’t improvise.

With Photoshop, there’s more artistic skill involved, but it’s still a purely technical function. My assistants are like construction workers—they don’t improvise. If I don’t supervise, they won’t know what to do. That’s why I dislike Photoshop and AI—it creates distance. Technology introduces a coldness that removes the warmth and direct connection to the work. For example, in the 1980s, when we watched Kung Fu movies, when someone bled on screen, it felt real. Now, with high-tech effects, when people fly through the air or fall from cliffs, it looks impressive but you don’t feel the pain—it’s fake. I prefer work that carries a sense of human warmth, a physical, emotional reality. I think this also reflects generational differences. Our generation values closeness, physicality, and emotional immediacy. Today’s kids often have no connection to animation or movies—they feel it’s fake. I can hardly be moved by it. It’s a strange thing, but it shows the limitations of people’s experience and perception.

Wang Qingsong The Blood of the World (2006)

Tami Xiang: So, for young people today, these limitations are really pronounced?

Wang Qingsong: Yes, exactly. People, no matter how young they are, or how much they think and imagine, are always concerned with the same things: life, aging, sickness, death… basically just eating, drinking, living, and dying. As long as someone is alive, there’s emotion. That’s just human nature. These are eternal themes. You can approach them in any way you like—it doesn’t matter. Even if you’re stubborn, like me, preferring analog methods over electronic ones, that stubbornness is part of the process. For example, when photography film companies were going bankrupt, I even bought a large freezer to store film for future use. I don’t mind taking only a few shots at a time; I could shoot the same film over decades. People can be strangely stubborn. It’s important, even if it’s “wrong” in a conventional sense. I choose my stubborn ways because they suit me. Nowadays, developing film is very difficult. Film labs rarely make money, so many have closed. You might be forced to choose other methods, but at the time, you may not even be interested in those alternatives.

Tami Xaing: How would you say globalisation has not only influenced your work but also Chinese culture as a whole?

Wang Qingsong: It’s very complicated now. The pandemic changed China’s international connections. At the beginning, there was fear; gradually people adjusted. But the economy stopped, and although everyone expected a rapid recovery, many people became apathetic—they “lie down” or give up. Foreign exchanges have slowed, and now it’s almost invisible. Exhibitions are rare, and economic activity is uncertain. Confidence is fragile. People used to think that with effort, problems could be solved and progress could be made—but now it feels like that effort might be wasted. Culture, art, and even the economy may undergo large and unpredictable changes. During COVID, people lost confidence. They stop striving because it seems too hard to improve their situation. For example, jobs pay so little that it would take forever to afford housing. People minimize their desires to survive, just enough to live day by day.

When I flew from the U.S. to Beijing before the pandemic, many people on the plane were early returnees from failed ventures. Now, after the pandemic, foreign visitors are extremely few—maybe ten people coming to Shanghai. So globalization, as it was structured before, has largely ended. Exchanges with the West are no longer like they used to be. Communication at the individual level may still exist, but large-scale international engagement has slowed dramatically. China now focuses more on internal consumption and economic circulation rather than reaching out.

Wang Qing Song Follow You (2013)

Economically, this shift has been significant. Confidence in the future and society, which existed before, is now hard to regain. Communication has become difficult. People may still communicate individually, but large-scale, meaningful exchanges are rare. We used to come together as a group, and it was normal for many people to participate. Now, it’s abnormal—like a public square where hundreds used to gather daily, including foreigners. Today, you might go three days and see no one. The pandemic changed everything. Social media grew massively because people couldn’t leave home. Everyone relied on phones and delivery services. Transportation like high-speed rail became faster, but the journey lost its richness—you go directly from station to station, and you no longer experience the small joys along the way. Life became more monotonous. During the pandemic, people lost hope. Many felt that years of effort could be wiped out instantly. Some even stopped having children or pursuing relationships. The world seemed to freeze, and encouragement or motivational talk felt meaningless. But China is a special case. With its huge population, a different kind of change may emerge—a new social or cultural response. Even if some people give up, a new generation may awaken and take action. For example, last year I organized an exhibition called Young Friends Come Together, inviting people born in the 1990s, mid-90s to around 2000. I asked them questions about life, values, marriage, love, careers, and art—questions many young people find annoying. Their answers were fascinating. Even if it seems like this generation is “lost,” there may be potential for something new to emerge. But online interactions are different now. People are much more direct, often aggressive. They may publicly attack opinions they disagree with. Relationships are different; respect and restraint have decreased.

Teachers are cautious too. When grading students, even if there are mistakes, there is a demand for high scores because of fear of repercussions. You can’t openly encourage or criticize. Everything is approached carefully. In short, the younger generation online behaves differently. They don’t care in the traditional sense, but this also means they may create new forms of expression. For instance, group shows, exhibitions, and collaborative projects still happen—they just happen in new ways.

Wang Qing Song Solo Exhibition, Everlasting Inscription, is displayed at UWA’s Cullity Gallery, from Decemebr 2025 to Early Febuary 2026.