“Because we’re equal”: An interview with Liu Zheng

22 July, 2025

Liu Zheng is a towering figure in Chinese contemporary photography (in fact one of his works is our current homepage background). Well known for his signature greytone style, a running theme throughout his work is an attempt to characterise his subjects through socially and politically provocative scenes. In this, Zheng attempts to capture the ‘real’ China, whilst also ensuring his subjects are not trivialized but rather elevated through his art, whether they be people, wax figures or landscapes.

Yet to introduce Zheng through his art is to omit the raw emotion and sincerity of his character. Packed into his small studio on the outskirts of Beijing, the interview began with awkward laughs and smiles, and ended with tears in our eyes. Zheng's willingness to open himself up, and speak with a clear sense of sincerity was something truly unique in the canon of artists we interviewed.

Although his words may seem overtly pessimistic in his review of the current state of Chinese contemporary art, Zheng's tone was always underlined by a sense of optimism. The words of Tami Xiang support this, whoes own personal experience elevated the impact of this interview.

We thank Liu Zheng for his time, and hope to see him again one day soon.

Liu Zheng Two Homless Boys, Beijing (1998)

Tami Xiang: You’ve published the work of hundreds of artists in your photography books. Has this affected your own work in any way? Has it influenced your creative process? Or has it perhaps even strengthened your own art?

Liu Zheng: To be honest, it hasn’t really affected me that much. I still test and explore my own things. It’s just one part of my work—sort of my contribution to archive Chinese contemporary photography. It’s more about organizing and documenting, for the future. Maybe it'll make things easier for someone who becomes a photographer later.

Tami Xiang: Can you share a bit about your main projects or works?

Liu Zheng: My works? Honestly, I’ve almost forgotten them. These days, I’m seriously thinking more about painting. Photography has become really disappointing to me—both in the context of China and globally.

When my gallery helped me organize an exhibition in Sydney, it had already been open for 20 days—and not a single person asked, “How much is one of your photos?” Not one. That tells you—they didn’t even consider the idea that photography could be sold. You understand?

That kind of situation is something I couldn’t have imagined 20 years ago. Now people just assume photography has no value, that it can’t be sold. In China, I know many gallery owners—many are close friends—but very few work with photographers. It’s extremely rare.

Most galleries in China, and their owners, know nothing about photography. That’s just the reality. So painting still has some space, but the photography market in China has almost completely collapsed. Now, those with some capabilities have shifted to curating or seeking funding from the government or wealthy individuals just to survive.

I don’t know what the situation is like where you’re from but there are so many good Chinese photographers—we should pay more attention to them. But now, some of them have started delivering food for a living. Our photographs are becoming more and more worthless. In China, they’re worth nothing. Maybe that’s just my situation—maybe others are doing fine. I don’t know. But I really think China hasn’t built a healthy system for photography. There’s no real system for collecting works I know many major photography collectors in China, and almost all of them have stopped collecting. We’re still friends, still have dinner together—but they’ll never buy a photo again.

It’s a mess.

I’ve still been working—I’ve been shooting landscapes for the last 10 years. I have four photography books coming out. Maybe in two months, you’ll see them. I’ve never stopped thinking about photography—not even for a day. But now, I’m starting to shift away from it. I’ve always paid attention to the Chinese and global art worlds. I care about things related to China and different media. I started with photography, so naturally I care about it. Even though I work in other media now, photography is still the most important field I care about. It may seem like I’ve distanced myself from it—working in art museums, doing all kinds of things—but one day, I’d still like to take a few Chinese photographers and tour the world with them. Just a few, the ones I really like. The rest—forget it. That’s my goal.

So that's my motivation. Even though I’ve moved into other media, photography will always be what I care most about. And I want to keep bringing Chinese photographers to the international stage. Even if I wasn’t a great photographer myself, I still want to do that. As long as you're all here, there's still hope.

Really.

That’s the truth. Because in China, I can’t find eyes that truly look at art sincerely. I just can’t. All my most moving artistic moments happened abroad, 20 years ago.

Thank you, truly—thank you all for coming.

Liu Zheng An Old Peking Opera Actor Playing a Female Role Beijing (1995)

Tami Xiang: Thank you. Thank you.

Could you further explain the reason for photography’s marginalization in China from your perspective? What influences have contributed to photography being misunderstood and kept separate from what’s considered “real” art?

Liu Zheng: Yes, yes, that’s a very well-phrased and accurate question. It truly reflects the situation in China right now—and, to some extent, globally as well. A big reason is the development of technology—smartphones, the internet and AI—these things have made photography something that anyone can do. That’s irreversible.

As a result, photography has undergone a huge change in nature—it’s no longer considered a form of art. Now, everyone can use their phones to take photos—anyone can. That’s had a huge impact, and it has led to misunderstanding because the word “photography” no longer carries the same meaning as before—it’s now a completely social and mass-consumed concept. And photography artists don’t have a real chance to explain themselves or their concepts.

For example, look at the Lishui Photography Festival. If you took people there, they’d be overwhelmed—over 3,000 exhibitions. Government promotion turned photography into a cultural activity, not an artistic one. That’s a big challenge, and it’s excluded photography from the mainstream art world.

That puts photography in a very awkward position. It’s been pushed out of the realm of mainstream art—it’s no longer accepted as part of the fine arts world. That’s the current state in China, very clearly.

Liu Zheng Convicts Fetching Water, Baoding, Hebei Province (1995)

Tami Xiang: How has digital photograph impacted the value of traditional photographic methods, especially darkroom printing and analog film, given these older processes have a limited quantity to them, and require more skill and craftsmanship.

Liu Zheng: Yes, yes, you’re right—digital photography has had a big impact on traditional photography, especially film and darkroom techniques. Those older methods had a kind of uniqueness due to the limitations of analog formats—they had edition limits.

Yes, traditional prints are more valuable, but fewer people are interested—they don’t have the time, money, or experience. Young people in China can’t afford it, even though it’s freely available here.

I actually still have a darkroom here. I use it to teach people about photography and darkroom processes. Anyone who’s interested can go check it out—students sometimes come to develop photos there.

Traditional photography definitely holds more value now—but too few people are willing to try it, because it’s more difficult. It takes experience, time, and money. Many young people just don’t have the conditions to pursue it. My darkroom is free—anyone who wants to try is welcome. But even so, very few people come.

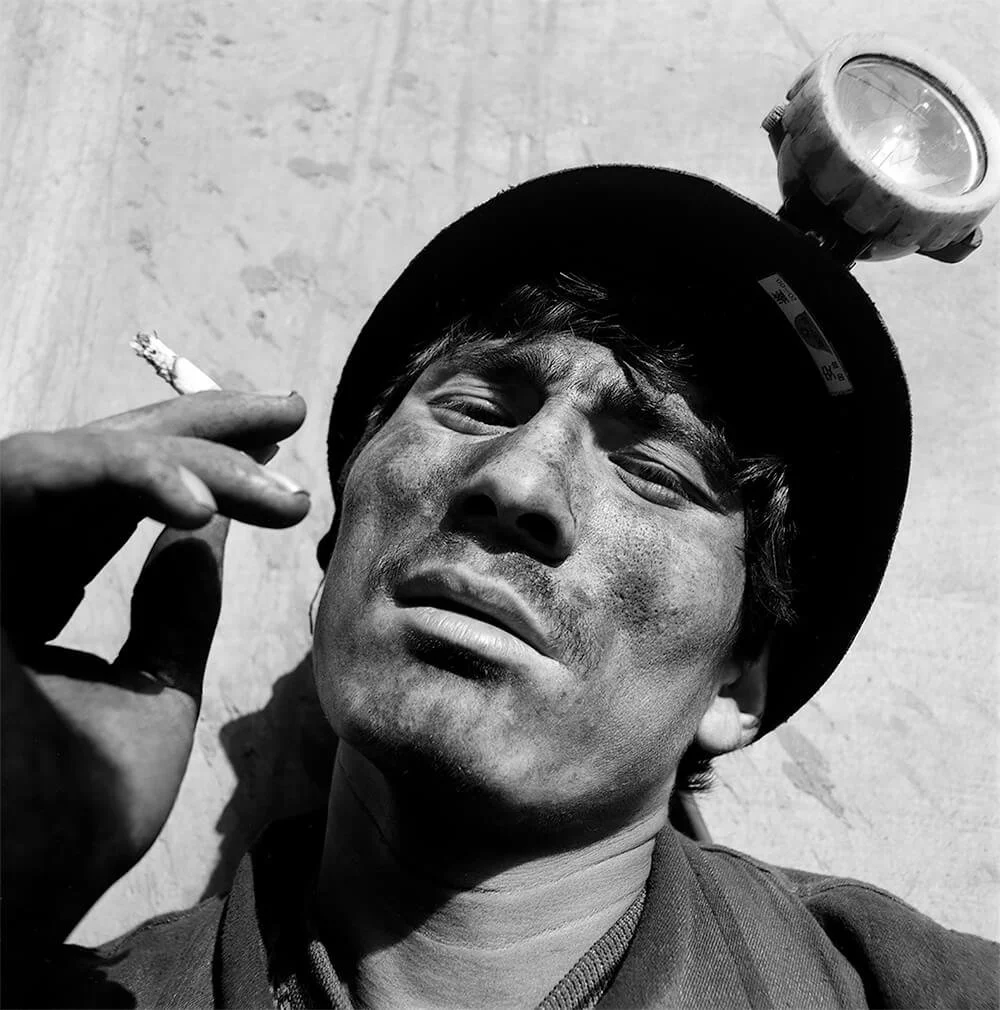

Tami Xiang: There was an interview where you spoke about this—how you build trust with people when photographing them. Can you say more about that?

Liu Zheng: I’ve always believed that people are equal. So, I rarely feel any distance or separation between myself and others. People often ask, “Why are you able to photograph them?” I say, “Because we’re equal.” When I show up, very few people reject or resist me.

Trust is something that has always come naturally in my work—I don’t have hidden intentions or selfish motives. Most people can feel that right away. Very few have ever refused or rejected me. Yes, people talk about things like “portrait rights” these days—legal stuff and all that—but I’ve never really encountered those problems. There’s always been trust between me and the people I photograph.

Liu Zheng Coal Miner, Xinjiang Province (1996)

Tami Xiang: When photographing someone, is the moment of photographing more important, or the final image?

Liu Zheng: I often say this to others—what I care about most is that moment of photographing. That’s the most beautiful moment in my life. When people can trust and connect with each other, and when there’s mutual recognition—that’s one of the greatest affirmations of human value.

Much of what I live for is to find that kind of relationship. What you see in the photos is just a small part of what I’ve experienced. Photography is a way for me to connect with people across China. Only a few of those connections become deep and harmonious—but those are very meaningful to me. Photography is the medium through which I find those relationships.

But later on, things slowly started to change. For the first 15 to 20 years, I was mostly photographing people. For nearly two decades, my work was centered around building relationships with people.

Yet in the past ten years, I've primarily been photographing landscapes without people. Why? Because I've developed a sense of distance and even fear toward people. Over the past 20 years, I’ve witnessed how the hearts and minds of Chinese people have changed—people have become increasingly complex, and sometimes even dark. These are things I find difficult to accept.

So during my interactions, I really experienced too much misunderstanding and hurt, gradually. And I started avoiding people, shifting my focus to landscapes.

So, in the past ten years, I've been photographing a China without people.

Tami Xiang: Thank you. I really resonate with what you’ve said. I, too, deeply love this land. Like Mr. Liu, who has had a great influence on my work—he’s an artist I met ten years ago, someone I really respect.

We are all Chinese people who deeply love this land. And it's through getting to know my predecessors that I began using photography to try to bring some awareness. So I deeply relate to what Mr. Liu said. I, too, have been hurt by many Chinese people, and I eventually stopped speaking out. Many of us did.

So, what I want to say is—I really resonate with what Mr. Liu has expressed. He’s one of the most respected photography artists I’ve met. When I met him ten years ago, he greatly influenced me—my values, my understanding of art.

Back then, all my work was about scenery. But after meeting him, I realized photography and art could awaken something in people. I wanted to give a voice through that. But over the years, I was hurt too—and like him, I tried to escape. That’s just the reality of being an artist in recent years, especially with the disappointment we’ve faced in the actions of our fellow citizens.

Liu Zheng: Yes, we met ten years ago in Linzhou. I remember when we first met—others didn’t even want to introduce us. They tried to block our connection. Maybe that’s what Chinese people are facing now: barriers between each other.

Liu Zheng Waxwork: Emperor and Girl in Fornication, Changping, Beijing (2000)

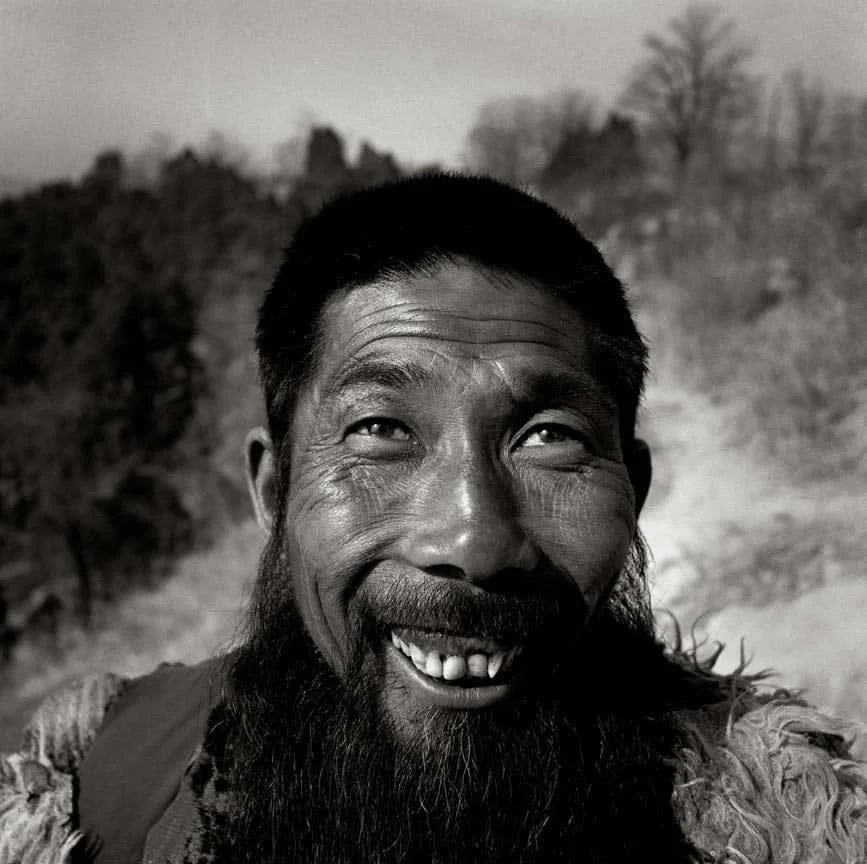

Tamin Xiang: Could you tell us about your "Guoren" (National People) series? It seems like it was an attempt to define China at a specific moment in time—like what Walker Evans tried to do in the U.S.

Liu Zheng: Yes, that's one of my most important works. That series was indeed trying to define China during a specific historical period. In that sense, it shares similarities with Walker Evans. When I began that project, like Evans, I was doing work with a strong social documentary aspect.

Evans worked for the U.S. Farm Security Administration, and I also started with a goal of documentation. But during the process, both of us gradually moved away from that initial social aim and began a deeper, more personal exploration. We moved toward something abstract.

My "Guoren" project took seven years to complete. It took me seven years to complete that project.

It started in 2000—well, from 1995 to 2002. That was when I was photographing the Chinese people, influenced by thousands of years of Confucian culture. What I wanted to capture was something different from the real China—something more abstract. A kind of defense or representation of the Chinese spirit.

You know, traditional documentary photography often just follows what people say—what they claim to be real is accepted as real. But I was trying to build something more abstract.

So, what I really wanted was not just a realistic portrayal, but a conceptual collection of images—a kind of abstract China that transcends the real. Just like Evans eventually moved beyond reality into an abstract world.

Honestly, I haven’t really talked to anyone in a long time. These past ten years, since the pandemic, I’ve been dealing with moderate anxiety and depression. I don’t even know how many times I’ve cried—this month alone, I've cried almost every day.

Nobody understands. This world... this country... sometimes I feel like there are no real people left.

Tami Xiang: Mr. Liu, I think you are a true patriot.

Not the kind of nationalist that hates other countries, but the kind that truly cares about the people and the land of his country. That's what real patriotism should be.

Liu Zheng: Yes, but I have no country—only land. That’s what I meant. There’s a distorted nationalism now, where people express patriotism through hatred of others.

I think about this all the time. Whether it’s all worth it. But what you said really moved me. That’s the power of art, isn’t it? It brings out shared feelings and reflections in people. Our art is about finding others who resonate with that same emotion.

Liu Zheng Three Women at a Country Funeral, Longxian, Shaanxi Province (2000)

Tami Xiang: Let’s move on to the next question. Could you talk about the continuity between your famous work "The Chinese" and your later "Selfie" series? It seems like there’s a shift from documentary to something more conceptual.

Liu Zheng: Yes, I can talk about that. In my creative process, everything has been very natural. I never really had a strict concept like, "this year I’m doing documentary, next year I’ll do conceptual work." It’s always been a continuous process—just earlier on, there was more reliance on documentary, on reality.

Each time, I would work within a defined scope to complete a project. But later, that scope got wider and wider. I stopped setting boundaries for myself.

As for the selfie project, you may not have seen it—well, you might’ve seen it at Lianzhou back then. They were very large-scale prints, downloaded from phones. They were photos taken by regular people—photography lovers—of themselves. And they were all nude. At that time, there was this unique channel in China where such work could intersect with art—it became an art form born out of that era in China.

But today, that would be impossible. Nude photos like that could never be exhibited in China anymore. Back then, dozens of giant nude photos could be exhibited—what an incredible time that was. Today, that’s no longer possible.

In my next phase of creation, I might include more painting elements. Just like someone mentioned earlier—traditional film photography has this "edition" issue, which seems to add more value. So I’ve been thinking: what if a photograph exists only as a single edition? Can that help resolve this issue of editions in today’s art world?

This is something I’m trying out. I don’t know if, in Australia, editioning affects the photography market as much?

Darren Jorgensen: In Australia, people generally sell works in series. Some photographers make mono prints or hand-colored black-and-white prints, which can add value. But if you had an original print—like one developed by Ansel Adams himself—it would be significantly more valuable than prints made by others from the same negative.

Liu Zheng: Ah, I see. In China, too, people are trying all kinds of ways to address this. Like making photography into a unique object—just one print. Otherwise, it’s a headache, because on this land (China), there has never really been a concept of trust. In fact, the lack of trust is so severe it becomes paradoxical. Because of editioning, many collectors just refuse to collect photography altogether. So we need to resolve this.

Liu Zheng Xinjiang Girl Working in a Textile Factory, Hetian, Xinjiang Province (1996)

Tami Xiang What draws you to photography over other mediums? From your perspective, do you consider photography to be a more impactful form of expression?

Liu Zheng: I studied science and engineering—specifically, camera manufacturing. As part of that, we had photography classes. I remember one day, during a class where we were enlarging a photo from slide film, the moment the image appeared for the first time—I remember it so clearly, even after nearly 40 years. That moment made me feel like this is something that could make me happy for a lifetime.

So I stuck with it. Later, of course, I came to understand that photography is a very complex medium—not as simple as I first thought. But that initial impact, that sense of possibility, that imaginative leap—that’s what has kept me on this path.

Even now, as I experiment with painting, I could never completely leave photography behind.

To me, photography is distinct from all other art forms. It has a unique power, a contemporary edge, and its own evolving artistic characteristics. It hasn't reached the point of decline, and I won’t abandon it.

What I hope is to create a hybrid between photography and other media—to express my ideas more clearly and powerfully.

Tami Xiang: Did the work of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado influence you, especially when you were documenting the struggles of the working class in China?

Liu Zheng: Yes, Salgado definitely influenced me. That was a long time ago—back in 1991. I saw his book at the time. What I really liked about it were the ways it abstracted human suffering and daily behaviour from very concrete labour scenes. There was even a kind of religious undertone in those images that really impacted me. He tried to extract the most abstract essence of human behaviour from the most ordinary, mundane scenes. That’s what influenced me.

Liu Zheng Actors in a Film about the War Against the Japanese, Lugou Bridge, Beijing (2000)

Tami Xiang: Can you talk about how your background in photography has impacted your work in other media? For example, how has it influenced the way you choose subjects or the way you express yourself artistically?

Liu Zheng: In the very beginning, I loved drawing—I was a painter. Before I turned 20, I focused on traditional Chinese painting. I really liked Chinese painting back then. But now I’m sick of it. I can’t stand it anymore. Whenever I see traditional Chinese painting or photography mimicking that style, I feel disgusted. I just can’t bear it—even though I’ve published some books in that style myself. There's a physical aversion now.

Why? Because, aesthetically and materially, that style doesn’t match the current era. The kind of humanistic condition that existed 1,000 or 2,000 years ago doesn’t exist anymore. So I’m now more interested in modern, contemporary, and objective forms of observation. I prefer that kind of aesthetic.

So when I photograph landscapes in China now, I’m not using the traditional Chinese aesthetic perspective. I approach it from a more geological or scientific point of view—trying to observe objectively. I think China really needs this kind of calm, objective perspective, stripped of the so-called “filter” of traditional Chinese culture.

I've always asked myself: How much actual value does traditional Chinese culture hold today? There are many aspects that we really need to reflect on.

Tami Xiang: So your landscape photography is more biological, geological, and technological—not about traditional cultural appreciation?

Liu Zheng: Right. I want to strip away the romanticism and take a more detached, clear-eyed view. Chinese culture has a lot of problems that need to be rethought.

Tami Xiang: That makes sense. It’s also a big difference compared to how some people glorify everything about Chinese culture—treating all of it as beautiful and untouchable, and rejecting any critique.

Liu Zheng: Exactly. That’s why we need to remove that filter and really look at what’s behind it.

Liu Zheng Three Elderly Entertainers, Beijing (1995)

Tami Xiang: How have your experiences living abroad influence your views and what’s your mindset when you return to China after going abroad?

Liu Zheng: It’s complicated. Very complicated. My son and grandson, they’re Canadian now—not Chinese. Sometimes I feel very conflicted.

I really do love this land because I was born here. I’m curious about the people and the history. But sometimes I really don’t want others to know I’m Chinese. It’s a very complicated emotional state. It's embarrassing, or I'm not willing for other people to know I'm Chinese, I think. Sometimes when I’m at the airport, and I see a group of Chinese people,, I just think, "Oh, forget it, it’s so sad." You know, it’s especially heartbreaking.

Sometimes I don’t want to understand this point and I don’t want to go abroad, you know? Because others will think, "Oh, it's a Chinese person," they are troublesome, hmm.

Oh, I don’t know, sometimes I think when I die, I’ll find a place overseas to bury myself,

It's scary to say that, but maybe I want to be overseas but not very often, because it’s very, very miserable, to say that that I'm Chinese.

Tami Xiang: I think Chinese nationalism is complicated issue. For most, there is not only a love of the land and the people, but also love for power, and the government

So It should be explained that we are different from those Chinese nationalists.

Liu Zheng: And we, as well as these people, love our country. But I think they still don’t truly understand what it is, they can’t understand. The story of China is too complicated. They’ve done so much evil work, really, I can’t stand it. Only by studying China’s history can you understand, it's terrifying.

Sometimes I think, if one day, when I’m old, what will happen? I will definitely find a way. But its so difficult to do anything, even with my a hundred or so thousand negatives. So, what am I going to do when I leave this land or leave this world? Maybe I need to find somewhere safe to preserve those negatives, I don't know where it's going to be.

You know, in the end, I’ll drill holes and destroy them. No, no, no, this is a big project, you can’t destroy it. It’s because it’s already been ten years, a lot of things have passed. Sigh.

This is the result of ten years of hard work. Should I say it like that? No, don’t be so pessimistic. It’s not pessimism. I don’t have a place to display it. Maybe in two months, there will be a gallery in the south, I can’t move it there, it’s too troublesome, too many people in the south.

Liu Zheng Rural Peasant, Yanan, Shaanxi Province (2000)